This past weekend in my message, “Praying Inward,” I explored the story of Elijah in 1 Kings 19 as a window into how prayer is both an encounter with God and, through God, an encounter with who we truly are. In Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, C. S. Lewis addresses a wide range of prayer-related topics. In letter 4, amidst a discussion of prayer and the omniscience of God, Lewis writes the following:

Ordinarily, to be known by God is to be, for this purpose, in the category of things. We are like earthworms, cabbages, and nebulae, objects of divine knowledge. But when we (a) become aware of the fact—the present fact, not the generalisation—and (b) assent with all our will to be so known, then we treat ourselves, in relation to God, not as things but as persons. We have unveiled. Not that any veil could have baffled this sight. The change is in us. The passive changes to the active. Instead of merely being known, we show, we tell, we offer ourselves to view.

C. S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1964), 20-21.

This unveiling is one of the most powerful aspects of prayer. We seek to know God, but God also seeks to know us. He does know all things, but our willingness to open ourselves to God—our willingness to be seen and known by God—is fundamental to the relational encounter with God in prayer.

At times, we hide ourselves from God, even though we may be aware that God knows us. But there is a difference between informational knowing and personal/relational knowing. We experience this in our lives every day. When someone inquires about how our day is going and we recount the facts of our schedule and events, this is not really what that person is asking about. They are asking about us—how we are doing, what we are experiencing, what it means to be distinctly “us” in the midst of this specific day.

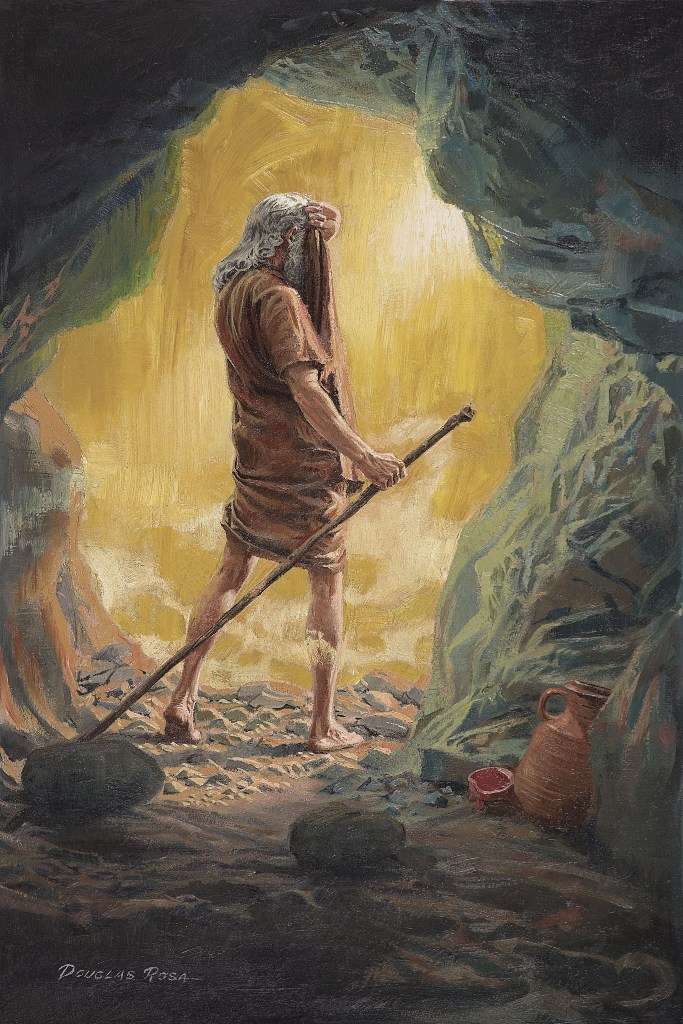

So, too, God desires to be known by us and also to know us. While God is not averse to knowing the information of our lives, God is already aware of all that. What God desires is to know the real us. Prayer, at least in part, is an unveiling of our lives to God. We reveal to God who we really are. Simultaneously, prayer is an encounter where God also unveils Himself to us, while also unveiling who we really are to us as we draw nearer to God. Increasingly, we lay down the masks that we carry or the fears and anxieties that grip us or the religious posturing that at times defines our prayer. In this more authentic, real place, we step out from behind all else to meet with the God who has made us for Himself and who knows us more than anyone else. in my message on Sunday, I described this as responding to God’s invitation to come out of the cave of ourselves and into God’s presence. This derives from Elijah’s encounter at Mount Horeb, where an invitation from God comes to Elijah, who has taken shelter in a cave:

The LORD said, “Go out and stand on the mountain in the presence of the LORD, for the LORD is about to pass by.” (1 Kings 19:11)

The invitation of God still beckons us to come out of the cave of ourselves, to choose to be unveiled and also to let God unveil us, as we meet with the God of the universe.

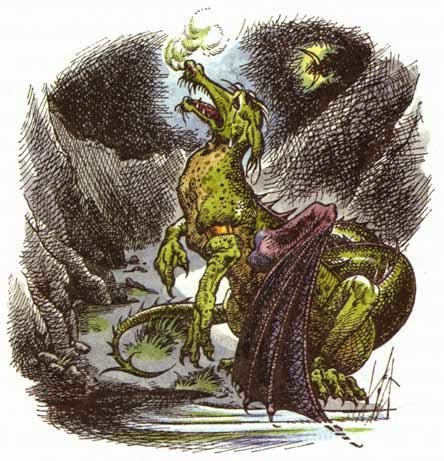

In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, one of C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia, a young boy, Eustace, is an arrogant and difficult companion for all those traveling together, including his cousins, Edmund and Lucy. When Eustace is turned into a dragon through his own foolishness, that external shape change sets him on a course to an internal heart change. Eustace’s pain and exclusion lead him into a humble place with others, what we might describe in Christian terms as a sort of repentance. With this change of heart, he is ready for an encounter like no other. Aslan the lion meets with Eustace on the far side of the island from where the travelers are docked, and invites Eustace to undress, to shed his skin. Unsure how to do that, Eustace scrapes off some layers of his dragon scales with only minor effect. Then comes Eustace’s unveiling, which he recounts to his cousins:

Then the lion said—but I don’t know if it spoke—‘You will have to let me undress you.’ I was afraid of his claws, I can tell you, but I was pretty nearly desperate now. So I just lay flat down on my back to let him do it.

The very first tear he made was so deep that I thought it had gone right into my heart. And when he began pulling the skin off, it hurt worse than anything I’ve ever felt. The only thing that made me able to bear it was just the pleasure of feeling the stuff peel off. You know—if you’ve ever picked the scab of a sore place. It hurts like billy-oh, but it is such fun to see it coming away….

Well, he peeled the beastly stuff right off—just as I thought I’d done it myself the other three times, only they hadn’t hurt and there it was lying on the grass: only ever so much thicker, and darker, and more knobbly-looking than the others had been. And there was I as smooth and soft as a peeled switch and smaller than I had been. Then he caught hold of me I didn’t like that much for I was very tender underneath now that I’d no skin on and threw me into the water. It smarted like anything but only for a moment. After that it became perfectly delicious and as soon as I started swimming and splashing I found that all the pain had gone from my arm. And then I saw why. I’d turned into a boy again….

After a bit the lion took me out and dressed me….he did somehow or other: in new clothes the same I’ve got on now, as a matter of fact. And then suddenly I was back here. Which is what makes me think it must have been a dream.

C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (New York: HarperCollins, 1952, 1980) , 107-110.

Prayer is an unveiling, an un-dragoning, of the self in the presence of God. Prayer is where we pursue God and know God more. Prayer is also where we surprisingly encounter ourselves more truly even as we encounter God.

Discover more from Matthew Erickson

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A beautiful story of a beautiful reality. Unveil and undragon me, God.